Connecting the Dots: Reflections on Data Use in Afterschool Settings

October 19, 2018

I have a confession to make: I am a data junkie, and I’m proud of it. The other day, a colleague forwarded an announcement by the Ballmer Group backing a project to give schools and social service workers technology to find and predict when kids need help like food aid, afterschool care and tutoring. (https://www.bloombergquint.com/business/2018/08/08/ballmer-sees-software-as-key-link-to-reach-at-risk-schoolkids#gs.nJ8_DUA ) I smiled and immediately clicked. The funding will help fund a software developer to set up projects in 20 cities connecting the company’s software to school data on things like attendance and grades. Alas, the smile faded at what I didn’t see stated clearly. Missing for me was the emphasis on the importance of people – users of the data of all stripes. Also, there was little clarity on how and why the technology will be used. Without a doubt, software can help manage information, but there are critical questions and groundwork that must be done before selecting software.

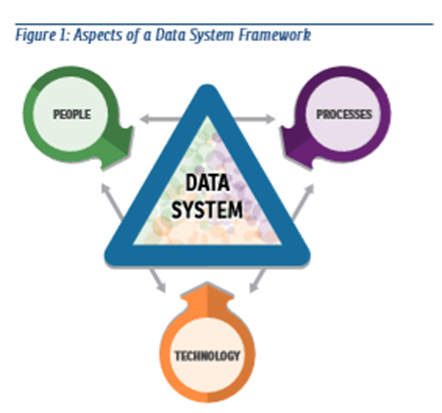

My reaction prompted me to revisit the Chapin Hall report, commissioned by the Wallace Foundation, “Connecting the Dots: Data Use in Afterschool Systems (https://www.wallacefoundation.org/knowledge-center/pages/connecting-the-dots-data-use-in-afterschool-systems.aspx).” This report is an analysis of a cohort of sites who worked on data sharing between school and afterschool systems. It was reassuring to see visually and in writing that the overall summary of the site work emphasizes the importance of people and process as much as the technology selected.

This overall finding was buttressed by other learnings that

- Context matters (e.g., is there a new superintendent? Is there an existing inventory of services for students? Is there a community history of partnering or using data?).

- Data elements should reflect system priorities (i.e., more information collected isn’t always better; a caution on asking for too much information and not using it).

- Building capacity and stakeholder engagement for use of data needs to be intentional (e.g., keep those entering data, creating data and community members involved throughout design, training and use).

- Change is constant, so be prepared and flexible (e.g., new technology options, new leadership with new priorities, policy changes).

The history of implementing new interventions, including technology, is littered with the skeletons of good intentions and products being malnourished after their introduction. I’ve left several myself as I reflect on an effort about 15 years ago to introduce the exciting capacities of SharePoint to a large state agency involving state staff from several departments and county government across the state. If I only knew as much then as I do now. Too much attention is paid on identifying the “new fix” and too little on its long term successful implementation, including answering a key question of “Are we (all of us) really ready to take this on?”

I remember talking with the chief technology officer of a state education department 10 years ago. This department had an excellent reputation for its longitudinal database, with dedicated staff in schools to use it. He found that by starting to support user groups with school staff, use increased dramatically. When asked about the ability to share education data with other departments, his response was that “the technology can be figured out in 2-3 months, but it will take your systems two years to agree to data definitions”. Another example of the need to pay attention to people (getting users support to build capacity to use) and process (reaching agreements on what “it” means).

The Chapin Hall report confirms the important factors of leadership at all levels, coordination of efforts, setting early norms and routines, engaging those with technology expertise early in the process and maintaining strong partnerships. In the end, we all need to remember that data and information are useful in helping users answer some questions and then ask the next set of questions. Technology helps, tremendously, but only when done well and deliberately with broad engagement. Good information promotes the possibility of transparency, which is critical to continuous improvement. But in the end, technology always needs to be the servant of people and agreed-upon processes.